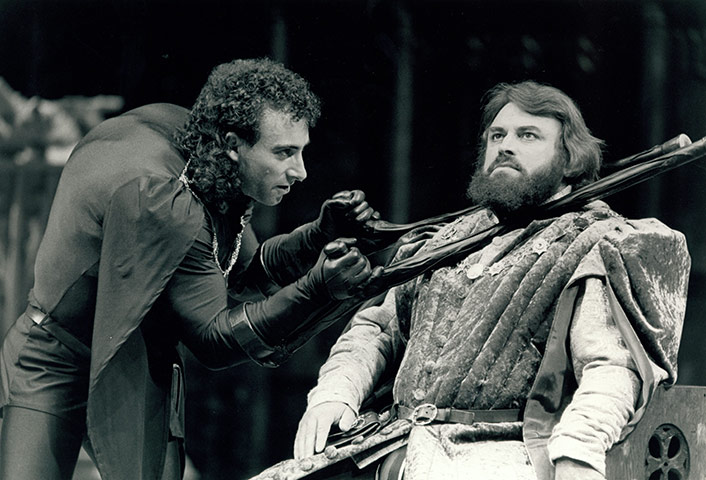

I’ve just finished Year of the King, by Antony Sher. It’s his diary/sketchbook from the year when he was working on Richard III at the Royal Shakespeare Company. It’s been on my to-read list for ages, so long, in fact, that I can’t recall who recommended it to me. It’s a fascinating look into his process as an actor, and how he blends his considerable skills as a visual artist with his work on stage. It’s definitely worth a read for anyone who works in theater.

One thing I found rather hilarious is that the politics, insecurities, and foibles of the RSC remind me so strongly of any theater I’ve ever worked in–even the greats are, apparently, not immune to these petty stumbles. In one particularly hilarious section, a group of actors and directors get into a days-long fight over whether the RSC has “an official policy on speaking verse.” Perhaps that’s only funny to someone who has been involved in that kind of conversation before, but to me, it was hilarious.

Another part I thought was funny was how they’re always hounding the director to make some cuts from the play, and he’s just telling them to act faster. The RSC is sort of known for doing Shakespeare in a style that I’m not that into–big, clunky, pause-y acting that disrupts the rhythm of Shakespeare’s line. In the midst of all this arguing about whether there should be fewer words or fewer pauses, Sher records a quotation by George Bernard Shaw, sent to him by a friend. Shaw is writing about a Hamlet by Forbes Robertson:

“He does not utter half a line; then stop to act; then go on with another half line; and then stop to act again, with the clock running away with Shakespeare’s chances all the time. He plays as Shakespeare should be played, on the line and to the line, with the utterance and acting simultaneous, inseperable, and in fact identical. Not for a moment is he solemnly conscious of Shakespeare’s reputation or of Hamlet’s monumentousness in literary history; on the contrary, he delivers us from all these boredoms instead of heaping them on us.”

I found that both lovely and surprising–lovely because it’s, in my opinion, the only way to get through a Shakespeare play, and surprising because it comes from Shaw, whose writing demands massive pauses, if only to accommodate his extensive stage directions.

And now I’m itching to do some early modern drama again.

Be First to Comment